It used to be called the American and Chinese War Crimes Museum. However, the name was recently changed to avoid offending two of the biggest tourist groups to come to Vietnam, and now it goes by the name of the War Remnants Museum. There are limits to how far state propaganda should interfere with money-making capitalism, I guess. (One has to wonder how the French avoided being part of the original name, since they started the whole thing.)

Anyone looking for a fair and balanced look at the Vietnam War (btw, the Vietnamese refer to it as the American War) would best be served elsewhere. By the time you got through with all of the exhibits you’d think the Americans were demon-spawn and the Viet Cong cherubic angels of innocence who came south to spread goodwill to all. It’s almost easy to forget who invaded whom.

That said, it was well worth the visit. Some of the material was truly disturbing, and there’s no question that many mistakes were made—no one came out of the conflict smelling like roses. And one of the exhibits in particular, honoring all of the photojournalists who died covering the war, was exceptionally moving. There are times in history that seem to bring out either the best or the worst in human nature; sometimes both.

And hey, John Kerry even had his picture featured there. Small world!

There was one area of the museum that promised to show “tiger cages,” a kind of prison cell used during the war. I followed the signs and came to this heavy metal door, which was padlocked shut. Darn. I figured the exhibit must be closed, but then noticed that there was a shutter open on the door at eye level.

Being ever so curious, I went over and peered into the darkness inside. As my eyes adjusted, I saw this grim looking man shackled to a cement block staring back at me. Whoa! They had a wax figure in a mock jail cell, but since it’s so dark you don’t realize that it’s not real at first. Scared the hell out of me, which I suppose is the intended effect.

Misery loves company, as the saying goes, so after my experience I was eager to see how other people reacted. Pascal showed up a minute later and I didn’t say anything, acting like I was standing around bored. He peered in as well and jumped back when he saw the guy. Heh, heh.

That afternoon we visited the Presidential Palace. That’s the one that famously had the tank dramatically smash through the front gate in TV footage during the 1975 fall of Saigon. They kept the place practically intact since then, with the phones and typewriters and wall maps with troop positions and all in the same condition as when it was captured. You could almost sense the bustle of activity that must have taken place there during the war. Kind of an eerie feeling.

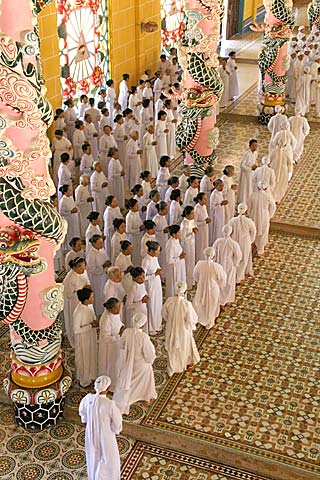

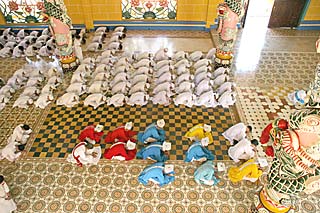

On Wednesday we left early towards the east, near the Cambodian border. In the morning we visited the Caodai Great Temple, for an obscure religion called Caodaism. The Lonely Planet has the best description for this place: “Built between 1933 and 1955, the temple is a rococo extravaganza combining the conflicting architectural idiosyncrasies of a French church, a Chinese pagoda, Hong Kong’s Tiger Balm Gardens and Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum.” Amen.

I’d never heard of Caodaism before, but it’s apparently a potpourri of all the major religions, an attempt to take elements from each to create the “ideal” religion. I wonder if they grabbed that 72 virgins martyrdom bonus from Islam while they were at it, since the Caodai haven’t been exactly blessed on the religious tolerance front. The temple was quite a trip, plus we saw an entire procession of monks and nuns (average age: 106) starting their daily prayer service and chanting.

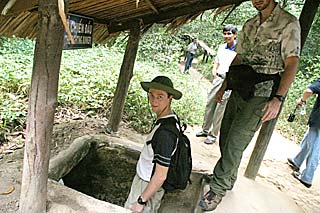

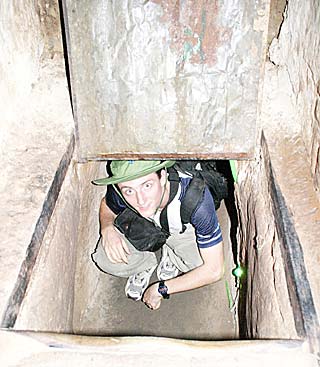

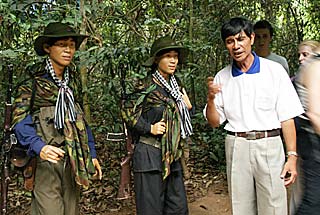

In the afternoon we visited the Cu Chi tunnels. The Vietnamese dug hundreds of miles of tunnels running all the way from Cambodia into Cu Chi province, which supplied the Viet Cong attacks on and within Saigon. They were one of North Vietnam’s greatest military successes, and a bane to the South and the American forces.

In fact, the tunnels were so effective in the mid-60s that a North Vietnamese victory seemed a very real possibility, prompting President Johnson to send American troops to Vietnam. So in some respects the tunnels are directly linked to US military involvement in Vietnam.

The South Vietnamese tried to relocate all the villagers to camps to eliminate the effectiveness of the tunnels. Didn’t work: the VC tunneled right into the camps and took control from within. The Americans set up a base in Cu Chi, locating the 25th Infantry Division there. Tens of thousands of men were unable to put an end to the weapons and people smuggling. In fact, the VC tunneled right into the American base camps and wreaked havoc at night.

Then came Agent Orange, used to defoliate the entire area. Even that didn’t stop them. After the trees had no leaves, the area was sprayed with gasoline and set on fire. Didn’t work either.

Then the Americans sent men into the tunnels, “tunnel rats.” As you can imagine, between the frequent close quarter firefights and countless booby traps, the casualty rate for these men was ridiculously high.

The dogs were next, but the VC resorted to pepper to throw off the German Shepherds, and started washing with American soap and wearing captured US uniforms to confuse the dogs. Plus, the dogs were getting killed by the dozens by booby traps as well. So that didn’t work.

Finally, the entire area became a free-strike zone, and B-52s bombed the place to oblivion. That had the most impact on the tunnels, leading some historians to call the Cu Chi area “the most bombed, shelled, gassed, defoliated and generally devastated area in the history of warfare.” But by this time the war was practically over.

30 years later, they’re a tourist attraction. Funny how history works, isn’t it?

In order to make them more quickly and to avoid tunnel collapses, the tunnels were small. Pascal and I duck-walked through most of them, and had to move on our hands and knees at some points. Other tunnels (which we couldn’t visit) required belly crawl, with some stretching for miles and requiring some 12 hours of crawling to get to the next station. Insane.

Plus, it was bloody hot. It was hot and humid outside to begin with, but by the time we’d spent even just a few minutes in the tunnels, we were dripping with sweat. I can’t begin to imagine the kinds of conditions the people that used and fought in these tunnels had to deal with. And let’s not forget the rats, snakes and scorpions.

Some other visitors that were in our group couldn’t handle it, and had to leave the tunnels immediately due to claustrophobia. The feeling of oppression was definitely intense. And some frankly just wouldn’t fit in the narrow passageways.

We also saw re-creations of a number of traps the VC used on the Americans—really barbaric looking things like pits with spikes and trap doors with spikes and swinging balls spikes. Come to think of it, sharp pointy spikes seemed to be a recurring theme.

By far the coolest thing we got to do, though, was at the firing range. Both Pascal and I bought bullets and shot a Russian-made AK-47 machine gun. I think we reinforced the stereotype of bloodthirsty, warmongering Americans with the other tourists that were there—mostly Europeans—as we were the only ones that decided to do so. With enthusiasm, to boot. They just stood around nervously and watched as we made minced meat out of the range targets. But come on, how often do you get to shoot an AK-47???

Our guide for this temple/tunnel trip ended up being a really interesting fellow as well. An interpreter for American soldiers during the war, he’d met both Bob Hope and Robert McNamara. After the war, he spent over 3 years in a “reeducation camp.” He was actually more fortunate than others—some spent as long as 14 years in the camps. You got a sense from hearing him talk that he’d once been a vibrant and cheerful fellow who had, through his life experience, resigned himself to a wistful, philosophical passivity to the events around him.

That night we went out on the town again (rock on!). Saigon really is a fun place. While I was reasonable (I like to think of it as wisdom) and went to bed after the dance club closed at midnight, Pascal didn’t amble back into the room until 5:00 AM, having found some other after-hours bars not far from our hotel. Let’s just diplomatically say that he wasn’t the fountain of liveliness the next day! And he must have made some new friends, ‘cause he was kind of depressed about leaving Saigon.

On Thursday we flew to Hue, in central Vietnam not far below what used to be the DMZ (de-militarized zone). Why they call it a de-militarized zone when it’s the area that saw the most fighting and most gruesome battles of the war is beyond me. Kind of like calling Manhattan the “rural farmland zone.”

The area all along the central coast had gotten hit pretty hard by storms and flooding, so we were a little concerned about the weather, but apart from being consistently overcast it wasn’t an issue.

In the afternoon we visited a local market. Wow, the smells are just unforgettable. Not necessarily bad (although there are some fish smells that don’t particularly agree with me), so much as intensely strong. Everything from fish to meat to spices to vegetables to coffee to fruits to trash. Nostril overload. But visually and culturally fascinating.

Since we were going to visit some battlefields the next day, Pascal was inspired to renew his military-style haircut, which had gotten unrecognizably shabby in the last few weeks. True to form, Pascal picked the place with all the cute hairdressers. Ha!

While Pascal was getting his haircut, I was sitting around aimlessly waiting for it to end. The owner, who from what I could understand from our conversation was the mother of the four cute hairdressers, asked if I wanted a shoulder massage while I waited. Is the Pope Catholic?!

I ended up getting more than I bargained for. There was a massage table in the back, and it was only after I laid down that I realized that all four hairdressers were going to massage my back, shoulders and arms at the same time! Good Lord, sometimes life is just too good to be true!

But Pascal ended up getting an even better deal. After his haircut was over, he got a 10-minute shampoo and head massage, followed by a massage with 5 people (the four hairdressers plus the owner), followed by a full manicure. What a phenomenal deal! By the time we left Pascal looked quite like the proverbial cat who’d swallowed the canary!

In the morning on Friday we boarded a bus at the ungodly early hour of 6:00 AM., destination DMZ. We saw some of the most important sites of the Vietnam War: Quang Tri, the Rockpile, Khe Sanh, Camp Carroll and so on.

Surprisingly, there’s almost no evidence that anything whatsoever happened at any of these sites: to someone who wasn’t there they look just like any other forested hill or valley in Vietnam—any remnants of the war, either in equipment or impact on the landscape, are long gone. But from a pure historical perspective it was interesting to see the places where so much history took place.

The museum at Khe Sanh was particularly interesting, not so much for its exhibits as for its guestbook. Apart from the obnoxious political pontifications from some of the guests, the comments from some of the actual vets that had returned to the site of the battle were highly moving. It’s difficult to reconcile their experience with the apparent peacefulness and downright ordinary-ness of the place now.

Khe Sanh was the site of one of the bloodiest and most controversial battles of the war. General Westmoreland and President Johnson were obsessed with protecting the base from being overrun by the North Vietnamese, in an attempt to prevent another Dien Bien Phu (where 10 years earlier the French were obliterated by the Vietnamese, the turning point in their involvement in the war).

In some prolonged and bloody battles during the Spring of ’68, besieged Marines were joined by a relief force from the 101st to defend the base from what would end up being a massive diversion from the real attack: the Tet Offensive further south. Over 500 US soldiers and marines and 10,000 North Vietnamese died in the vicious fighting, which made the covers of both Life and Newsweek magazines. While the US held, the base had no overriding military value and American forces abandoned the base in June of 1968.

On the coast we visited the Vinh Moc tunnels. Unlike the Cu Chi tunnels near Saigon, which were used for fighting and smuggling, these tunnels were used by the locals to live, to escape the warfare and bombing aboveground. They were correspondingly bigger (while I had to stoop the average Vietnamese could stand in them), and a number of babies were born in the tunnels. Very different feel from Cu Chi, with some beautiful tunnel openings leading right to the sea.

Last night Pascal and I tried to find the nightlife in Hue. From a local cyclo driver we found out about this one dance club. Indeed, the music was good and the place was packed, but we were the only foreigners in there and we stood out like sore thumbs. Plus, the looks we were getting from the other patrons could only be described as “deeply hostile.” Time to move on.

So we found another place and ended up playing several rounds of pool, in which our game progressively got worse and worse despite any possibility of excuse that it was alcohol, since we weren’t drinking.

Today is our last day in country, and we’ll rent out some scooters and explore our surroundings again before heading out tonight in a long succession of flights back home. All in all, quite an experience.

Cheers!

Gabriel